How to shock a badass woman chef

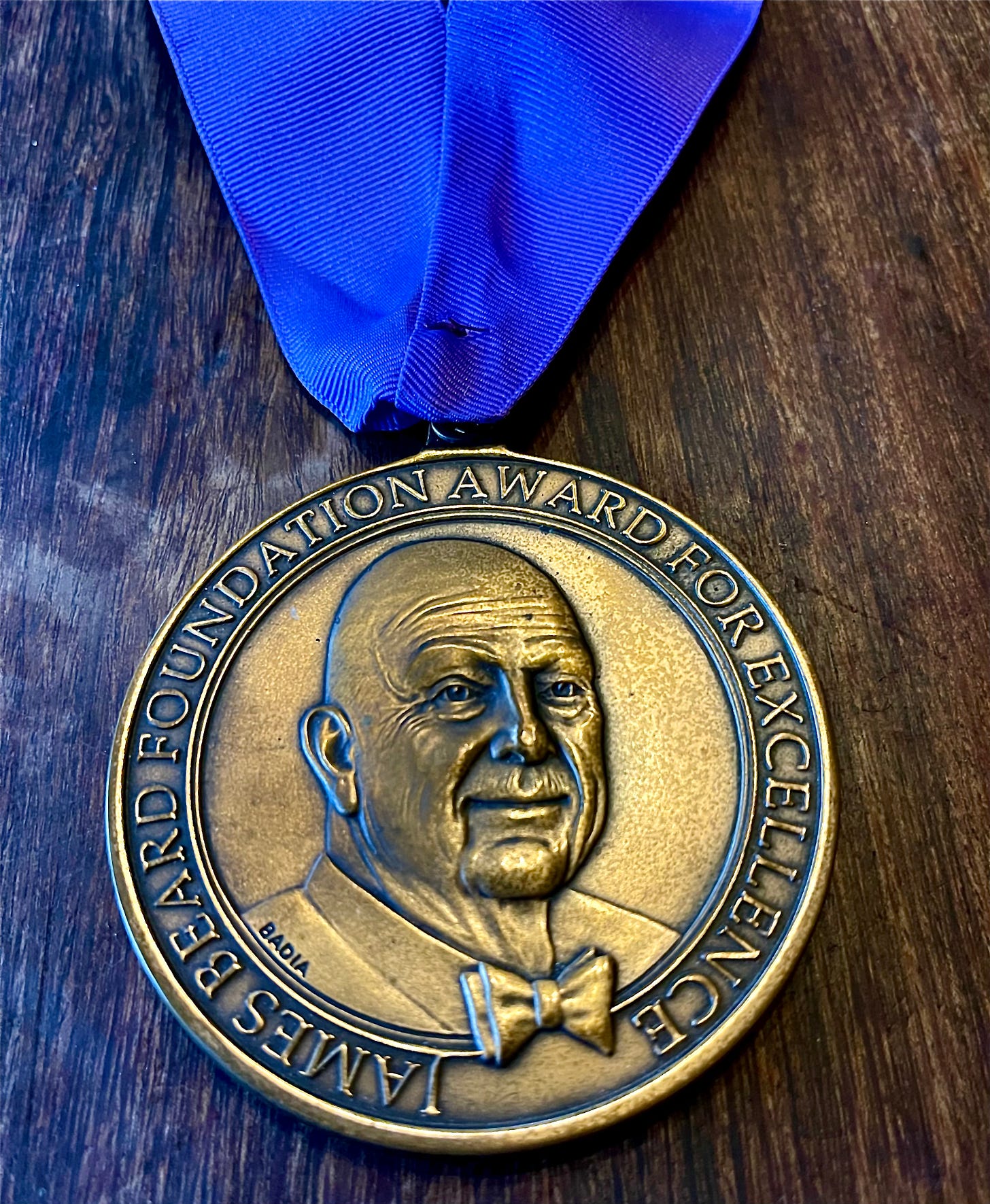

In our fourth episode, Nancy talks about winning the James Beard Award for Best Pastry Chef in 1991, and how aghast the presenter, French chef and cookbook author Madeleine Kamman, was that an upstart from California had beat out two famous men with French and Swiss training. The predicted winner was the legendary Albert Kumin, the original pastry chef of The Four Seasons who went on to work in Jimmy Carter’s White House kitchen and founded the now-closed International Pastry Arts Center in in Elmsford, N.Y.

“He is one of the only people I know who can labor relentlessly in the kitchen, covering the work of three, while remaining totally calm, good-humored and friendly,” Jacques Pépin once told Nation’s Restaurant News about Kumin, who died in 2016 at the age of 94.

Happily the other nominee is still with us. At the time, Jacques Torres was working at Le Cirque where he was famous for, among other things, his miniature edible stove. The youngest person to ever become a Meilleur Ouvrier de France, Torres was Dean of Pastry at The Culinary Institute for 30 years. Today he runs his own chocolate empire.

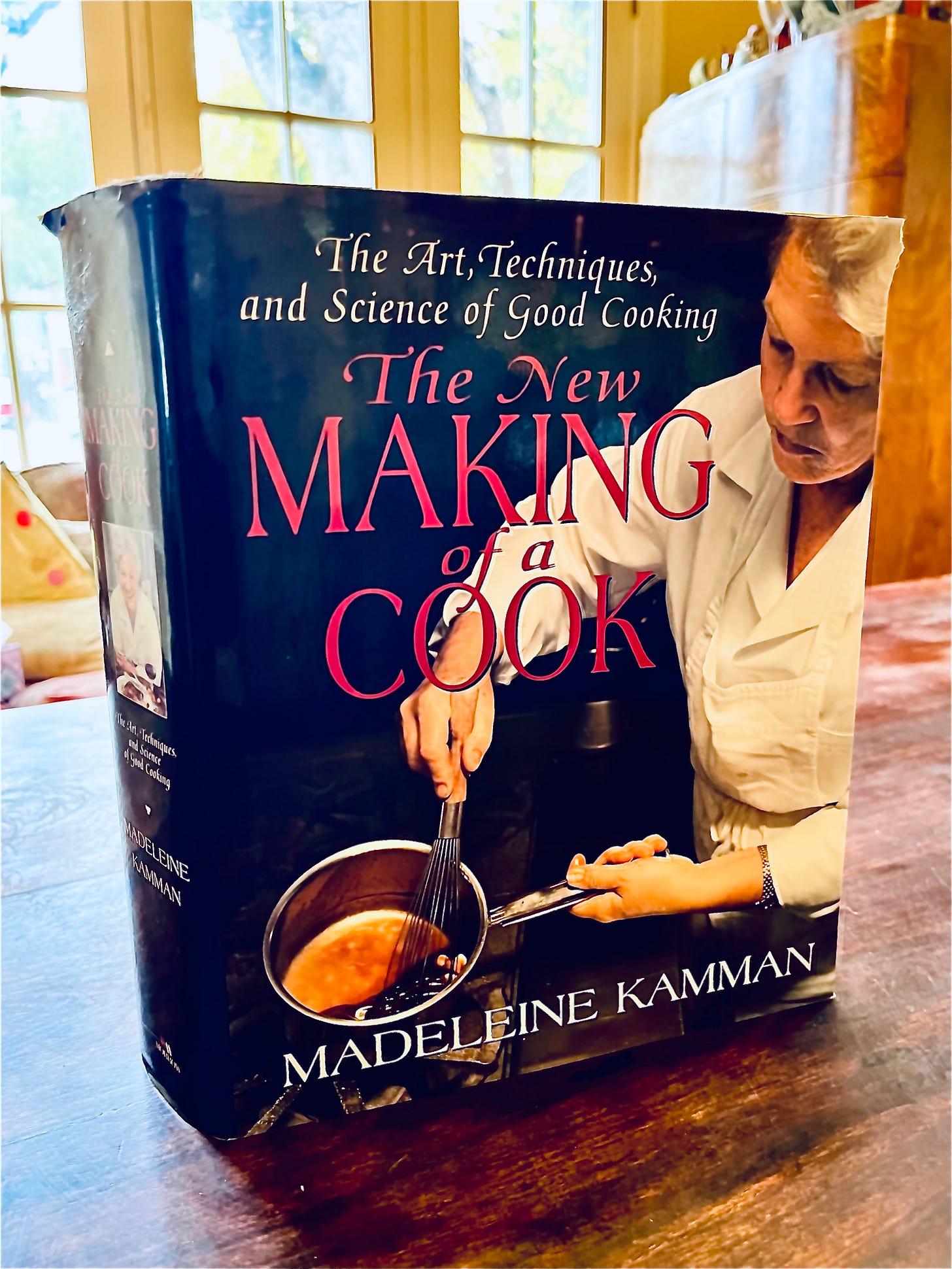

As for Madeleine Kamman … she was a complete badass. She was an outspoken chef, a champion of women and a legendary teacher. Paul Bocuse once called her restaurants “the best in America,” and she was the author of many books, the most notable being “When French Women Cook.” Laurie keeps a copy of “The New Making of a Cook,” the 1997 revision of Kamman’s first cookbook, on her shelf of encyclopedic cookbooks between Shirley Corriher’s “CookWise” and Marion Cunningham’s “The Fannie Farmer Cookbook,” with Julia Child’s “The Way to Cook” a respectful few books away since it’s likely neither of them would have liked to be beside each other.

Kamman had a famous rivalry with Julia Child. She pointed out that Julia was neither French nor a chef, but simply an American cooking teacher. Madeleine, on the other hand, was a trained chef with a successful restaurant who also wrote cookbooks and had a television show. “I am not for comparing people, any more than you can compare Picasso to anyone,” she opined with typical modestly. A few years ago Mayukh Sen wrote this article about her in the New Yorker.

What we like best about Madeleine? In 1990, she told the L.A. Times writer Rose Dosti that the next generation of great chefs would be American rather than French, and would consist of a 50-50 ratio of women and men. The 50-50 ratio hasn’t quite worked out yet, but Nancy’s win the following year at the James Beard Awards showed that the change Madeleine predicted was already underway.

That 1991 ceremony, by the way, was the first time the James Beard Awards as we know them were presented. Nancy had to remind Ruth that she had written about the ceremony — and about Kamman’s reaction to Nancy’s win — in the L.A. Times, not to mention at least one chef’s complaint about a young Wolfgang Puck winning Outstanding Chef of the Year. Here’s an excerpt:

“Like every awards ceremony, this one had its moments of controversy. Madeleine Kamman, who was sitting in the front row, shuddered visibly when Nancy Silverton was awarded the prize for best pastry chef over Albert Kumin, the dean of American pastry. ‘Albert Kumin changed pastry in this country,’ Larry Forgione of New York’s An American Place, said later. ‘His achievement should have been recognized. And if Chef of the Year was for career achievement,’ he went on, ‘why wasn’t Andre Soltner (the legendary chef/owner of Lutece) nominated?’ The answer seems to be that … the Beard Awards are centered on the food revolution that has swept America. … So it should come as no surprise that Chef of the Year went to America’s highest-profile young chef, Wolfgang Puck.”

It was actually a call Ruth received from New York Times reporter Julia Moskin that got our conversation started about the James Beard Awards. She asked if Ruth would comment on the organization after chef Timothy Hontzas of Johnny’s Restaurant in Homewood, Alabama, was disqualified as a best chef in the South nominee following an allegation that he habitually yelled at his staff and customers. (Hontzas told The Times that the incidents “were not as severe as the accusers described.” He also said that none of the incidents rose to the level of an ethics violation.) The disqualification, an action taken without consulting all of the restaurant awards committee members — who oversee the annual nominee selections on a volunteer basis — led one committee member and a separate judge to resign in protest.

Ruth declined the request for comment by Moskin, who teamed with Brett Anderson for an extensive story on the messy process of trying to make the James Beard Awards more equitable and diverse. The article opened with the organization’s investigation into an anonymous complaint about Kentucky-raised chef Sam Fore, whose TukTuk pop-up draws on her Sri Lankan family roots. Fore, who was surprised to discover that her social media posts advocating for victims of domestic violence were the subject of the investigation, said the process was “an interrogation.” Ultimately, she was able to remain a nominee in the Best Chef: Southeast category, although the award went to Terry Koval of The Deer and the Dove in Decatur, Georgia.

It’s not the first time the organization has come under scrutiny. In 2005, the president of the James Beard Foundation, Leonard F. Pickell was convicted of stealing more than fifty thousand dollars from the foundation. He was sentenced to one to three years and served about 9 months. He passed away two years later.

At this year’s awards ceremony in June, the restaurant awards committee chair Tanya Holland — who is also an acclaimed cookbook author and chef of the late great Brown Sugar Kitchen in Oakland (fantastic cornmeal waffles) — said from the podium that New Orleans legend Leah Chase once gave her some advice that seemed to apply to the stresses the organization is undergoing as it tries to find the best way to ensure the awards are fair and equitable: “‘Be prepared to get a lot of criticism in this industry, and work with it; you will make mistakes. The important thing is where your heart is and how you move on.’ The universe knows I’ve made numerous mistakes.”

L.A. Times journalist Stephanie Breijo, reporting on the ceremony, wrote that Holland told the audience “she has become comfortable being uncomfortable, adding that she is motivated to make the industry better. The efforts of the foundation have made a difference in the diversity of the awards’ nominees and winners, she said, and should be commended.

“We’re learning as we go,” Holland said. “It’s not always smooth, but that doesn’t mean we’re not on the right path.”

The endangered 20th-century restaurant

We move from the Beard Awards and a discussion about the mental stress and physical toll restaurant work entails, to an exploration of what makes a 21st century restaurant and how in many parts of the country 20th century restaurants such as diners are closing at an alarming rate. Laurie talks about the closing in May of Los Angeles’ Nickel Diner, which wasn’t technically a 20th century restaurant (it opened in 2008) but had a 20th century soul. Laurie wrote about her last meal at the Nickel, run by Monica May and Kristen Trattner, for the L.A. Times Tasting Notes newsletter. The table was loaded with scrambles, biscuits, homemade pop tarts and of course a maple bacon doughnut, plus marmalade made from blood oranges grown by the artist Ed Ruscha. Here’s an excerpt of the story:

All around us customers are giving hugs to May and Trattner as well as Nickel Diner’s servers, many of whom have worked at the Main Street spot for years and have become familiar faces. The customers also hug each other because it’s a kind of reunion for many who are part of the L.A. tribe in love with the diner and the tattooed punk-rock aesthetic that came with the place.

“We’re a 20th century restaurant,” May tells us by way of explanation of why she and Trattner think it’s the right time to close. Would they have stayed open if they had gotten one of their grants renewed to feed their neighbors living in the surrounding SROs or if inflation hadn’t raised their operating costs or if the pandemic hadn’t happened? Maybe.

But they also feel a change in the city. A few blocks away Suehiro Cafe, another 20th century restaurant that has been on Little Tokyo’s 1st Street for decades and may be the closest thing we have to a “Midnight Diner,” is being forced to move to a new location on Main Street, not far from the Nickel Diner. What difference will a move make? When I walked by the space Suehiro will inhabit later this summer I saw a now-hiring sign and noticed that one of the new jobs listed is “barista.”

Old-school Suehiro doesn’t have a barista. Apparently, 21st century Suehiro will have barista-made drinks. If it helps the place stick around for a few more decades, I won’t mind, as long as they still serve the okonomi plate with broiled mackerel and cold tofu. Because as Zen monk and teacher Shunryu Suzuki once told writer David Chadwick after he asked the master to summarize Buddhism “in a nutshell,” the answer came down to two words: “Everything changes.”

Eating off the cart

Finally, we talk about the safety of food carts. In 1995, when Ruth wrote an article for the New York Times about how much she loved street food, she included this interesting detail: “If the idea of eating at food carts frightens you, consider this. Fredric D. Winters, a spokesman for the New York City Health Department, said that of the 1,600 cases of food poisoning reported by doctors in the last three years, only 8 were said to be from food vendors. Only one case actually proved to be food poisoning, and even that case could not definitely be tied to a cart.”

You can read the entire article here. And in our bonus “Ingredients” post for paying subscribers, we’ll share Ruth’s recipe for a homemade version of the classic New York food cart dish, curry chicken and rice.

Ruffled feathers at the first James Beard Awards