We’re in Hawaii this week — at least Nancy is — and we talk about everything from native fruits to Spam, one of the few foods in the world that Ruth has never eaten. Ruth talks about the Zen of pie making, Nancy gives a shout out to two of her favorite kitchen utensils and Laurie waxes poetic about why Jonathan Gold fell in love with the island. Leaving Hawaii we discuss why failure in the kitchen is a good thing. Then it’s on to the politics of pesto — along with a handy little trick to make it better — even if you’re not doing it by hand.

Our favorite mortar and pestle

Nancy has shown up at the cooking class she’s conducting in Hawaii with just two treasured pieces of equipment. First and foremost is her beloved mortar and pestle, which is so heavy she’s asked her assistant Juliet to pack it in her suitcase. It’s one originally made for pharmacists and Nancy is so fond of hers that she sometimes buys extras to give to her friends. In fact, she gave one to Ruth years ago and Laurie has had one for decades too.

What makes it so special that all three of us have it in our kitchens? Nancy says that while a rougher molcajete is right for guacamole, she loves the smooth surface of her unglazed ceramic mortar and pestle for making mayonnaise, aioli and especially pesto, which she never makes in a food processor. Laurie found this description on the British Museum website that describes why the original Wedgwood & Bentley mortars were considered superior to marble “for the purpose of chemical experiments, the uses of apothecaries, and the kitchen”: “These mortars resist the action of fire and the strongest acids. ... They receive no injury from friction. They do not imbibe oil or any other moisture. They are of a flint-like hardness, and strike fire with steel.”

Nancy also loves her trusty Microplane. But then, who doesn’t? It pretty much changed life in the kitchen, as John T. Edge explained in this 2011 story for the New York Times.

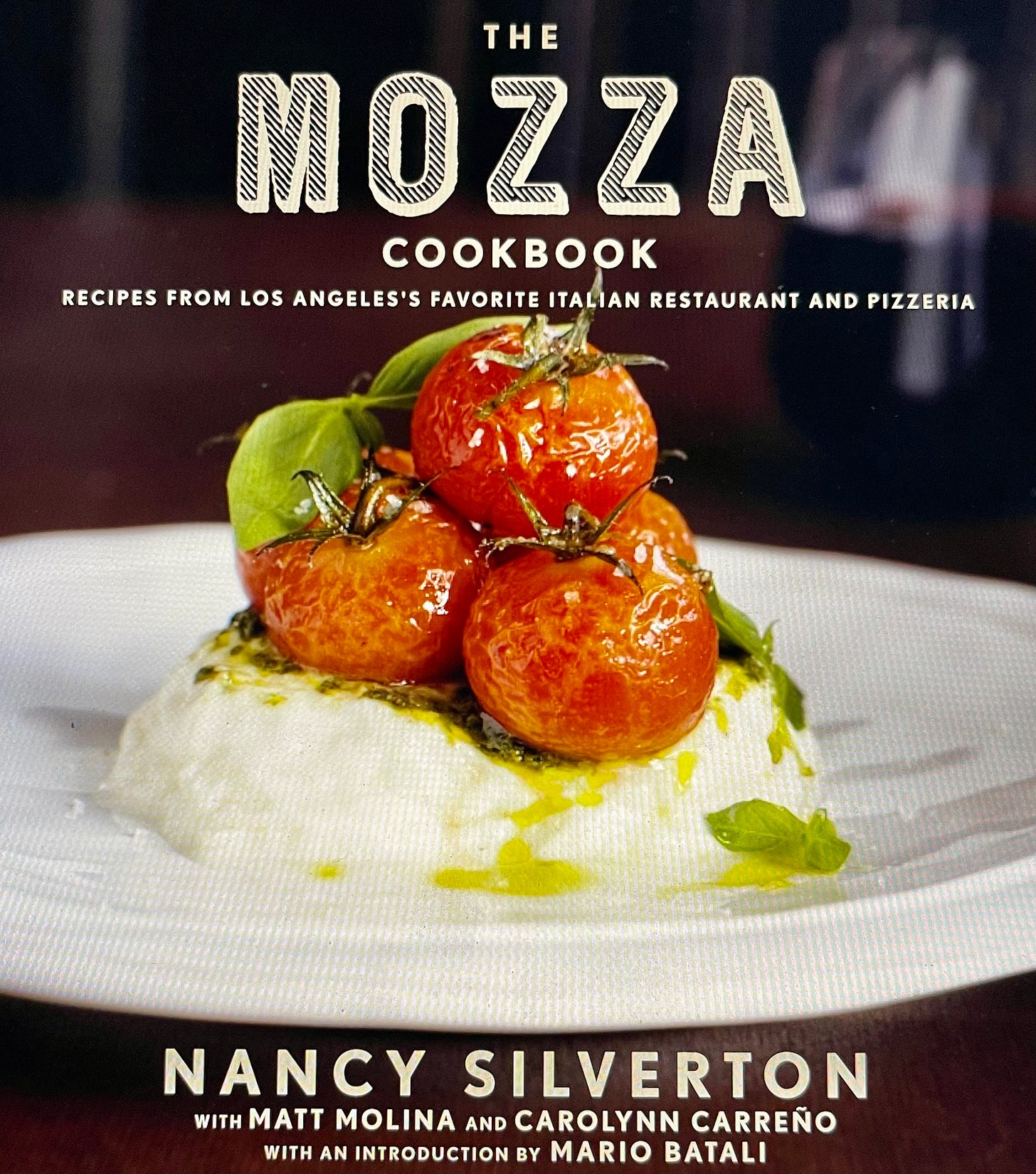

Note that in our bonus post for Episode 3, available to paying subscribers later this week, we share the recipe for Nancy’s caprese salad, which is on the cover of “The Mozza Cookbook,” plus a pie recipe from Nancy’s new baking book “The Cookie That Changed My Life” and a mini podcast all about salt.

A proper luau

Nearly every year Nancy participates in the Hawaii Food & Wine Festival, founded by chefs Roy Yamaguchi and Alan Wong. It’s an event that grew out of Cuisines of the Sun, which Associated Press writer Barbara Albright once described as “the ultimate food camp.” Nancy happened to be cooking at Cuisines of the Sun the year that Laurie took Jonathan to Hawaii for the first time. Until that trip in the late 1990s, Laurie had only experienced the food of tourist Hawaii and thought that the island destination would be a place where Jonathan could take a vacation from thinking about food in a serious way. Boy was she wrong. When they arrived on the Big Island they were invited to a luau that was unlike any Laurie had ever experienced. Held at Hirabara Farms run by Kurt and Pam Hirabara, who were pioneers in the Hawaii regional cuisine movement, the music, dancing and especially the food — all rooted in Hawaiian culture — were enchanting. There wasn’t a grass skirt in sight.

After that trip, Jonathan was smitten. Here’s an excerpt from a story he wrote for Ruth at Gourmet in 2000 describing that party:

There may be a prettier acre than Kurt and Pam Hirabara’s up-country farm on the island of Hawaii, where the damp, mounded earth and skeins of perfect lettuces glow like backlighted jade on a wet afternoon. But when the sun comes out and the mist melts away, and through a break in the clouds suddenly looms the enormous, brooding mass of Mauna Kea, the loftiest volcano in the world, it’s hard to imagine where that prettier acre might be.

Three hours before chef Alan Wong’s luau at Hirabara Farms, a party celebrating the relationship between the chef and the army of Big Island growers who supply the Honolulu restaurant that has been called the best in Hawaii, the tin roof of the Hirabaras’ long packing shed thrums with rain, and the thin, sweet voice of the late singer Israel Kamakawiwo’ole slices through the moist mountain air. Wong’s kitchen manager, Jeff Nakasone, trims purply ropes of venison into medallions for the barbecue, and pastry chef Mark Okumura slaps frosting on a stack of coconut cakes as high as a small man. Lance Kosaka, who is the leader at Wong’s Honolulu kitchen, arranges marinated raw crabs in a big carved wooden bowl. Mel Arellano, one of Wong’s colleagues from culinary school and something of a luau specialist, reaches into a crate and fishes out a small, lemon-yellow guava.

“I’ve got to eat me one of them suckas,” he says, and he pops the fruit into a pants pocket.

I nibble on opihi, pricey marinated limpets harvested in Maui, and try to gather in the scene. Two of Wong’s younger sisters stir a big pot of the gingery cellophane-noodle dish called chicken long rice; Buzzy Histo, a local kumu hula—hula teacher—crops orchids, exotic lilies, and birds-of--paradise brought over from the farmers market in Hilo. A cheerful neighbor, Donna Higuchi, squeezes poi from plastic bags into a huge bowl, kneading water into the purple goo with vigorous, squishing strokes until the mass becomes fluid enough to spoon into little paper cups. She giggles as she works.

“Some people like poi sour,” she says. “I like it frrrr-rresh. Although most people would say I’m not really a poi eater. I like it best with milk and sugar—it’s really good that way.”

Her friend stops measuring water into the poi and wrinkles her nose. “Don’t listen to Donna,” she says. “You try your poi with lomilomi salmon.”

If you’re hungry for more, here’s an article Jonathan wrote for Food and Wine Magazine, when he visited the islands with Roy Choi.

And here’s the L.A. Times story about poi that Laurie talks about in this episode. Poi is a food that most visitors to Hawaii rarely experience in the way it was intended to be eaten. “The mush you might have been served at a hotel luau,” she wrote, “was almost certainly not aged, and probably served plain, which is the rough equivalent of eating potatoes mashed without butter or cream.” Or, as Victor Bergeron, aka Trader Vic, once wrote, “Americans do not appreciate food which is too far out.”

Devil in a white can

Ruth, Nancy and Laurie all remember Underwood Deviled Ham with great fondness from their childhoods. Surprisingly, this is the entire ingredient list: Ham (Cured With Water, Salt, Brown Sugar, Sodium Nitrite) and Seasoning (Mustard Flour, Spices, Turmeric).

It turns out that it’s a very old product. The William Underwood Company began making it in 1868 (soldiers ate a lot of deviled ham during the Civil War), and the company’s logo was trademarked two years later making it the oldest extant American food trademark.

And what about that other ham in a can, Spam? As described on the Hormel website, it’s made from six ingredients: “pork with ham meat added (that counts as one), salt, water, potato starch, sugar, and sodium nitrite.” We talk about Spam musubi (Spam and sushi rice wrapped with nori), which has been popular in Hawaii for decades — Jonathan called it “the real soul food of Hawaii” in this review of the now-closed Monterey Park restaurant Shakas.

Ruth may not be a Spam fan, but our musubi talk prompted her to bring up one of her favorite nori seaweed-wrapped snacks, onigiri. We thought you might like to make your own onigiri. Here’s a recipe from Serious Eats.

For more recipes, including one prompted by Ruth talking about the zen of pie making — spending time with her rolling pin makes her very happy in the kitchen — check back later this week for this episode’s bonus post for paying subscribers with a new mini podcast.

Share this post